Winter oilseeds: Key to clean water and lower emissions

Organic farmer Karen Torjesen is one of the Minnesota growers who has planted the oilseed winter camelina. After planting in September of 2023, she had green growth — seen here — by early November. (Photo by Dodd Demas for FMR)

Pop quiz: How much of what we grow on farms is used for food?

Most of us think that farms grow food, and while that’s not wrong, it actually makes up a much smaller piece of the pie than in previous eras. About 40% of both corn and soybeans grown today in the U.S. are used to make biofuels. That means, when you drive through Minnesota’s 15 million combined acres of these two crops, much of what you see will eventually wind up in a gas tank rather than on a dinner plate.

In this way, agriculture and transportation are tightly intertwined. How we get around influences what we grow. And what we grow, and our agricultural practices in general, dramatically impact the Mississippi River.

This type of row crop agriculture is responsible for the “big brown spot” and is the primary contributor to pollution in our rivers, lakes, streams and other bodies of water.

We can go a long way toward fixing this by taking advantage of cropland acres we’re currently only using a few months out of the year. Doing this with promising new crops like winter oilseeds will cover the big brown spot with live plants and roots in the spring and fall — not just during the warmer months when corn, soy and other “summer annuals” are on the landscape.

By rethinking what we grow and when we grow it, we can shift the agriculture system towards better environmental outcomes and increase productivity without putting new land under the plow.

That’s where winter annual oilseeds come in.

A foundation for sustainable fuels

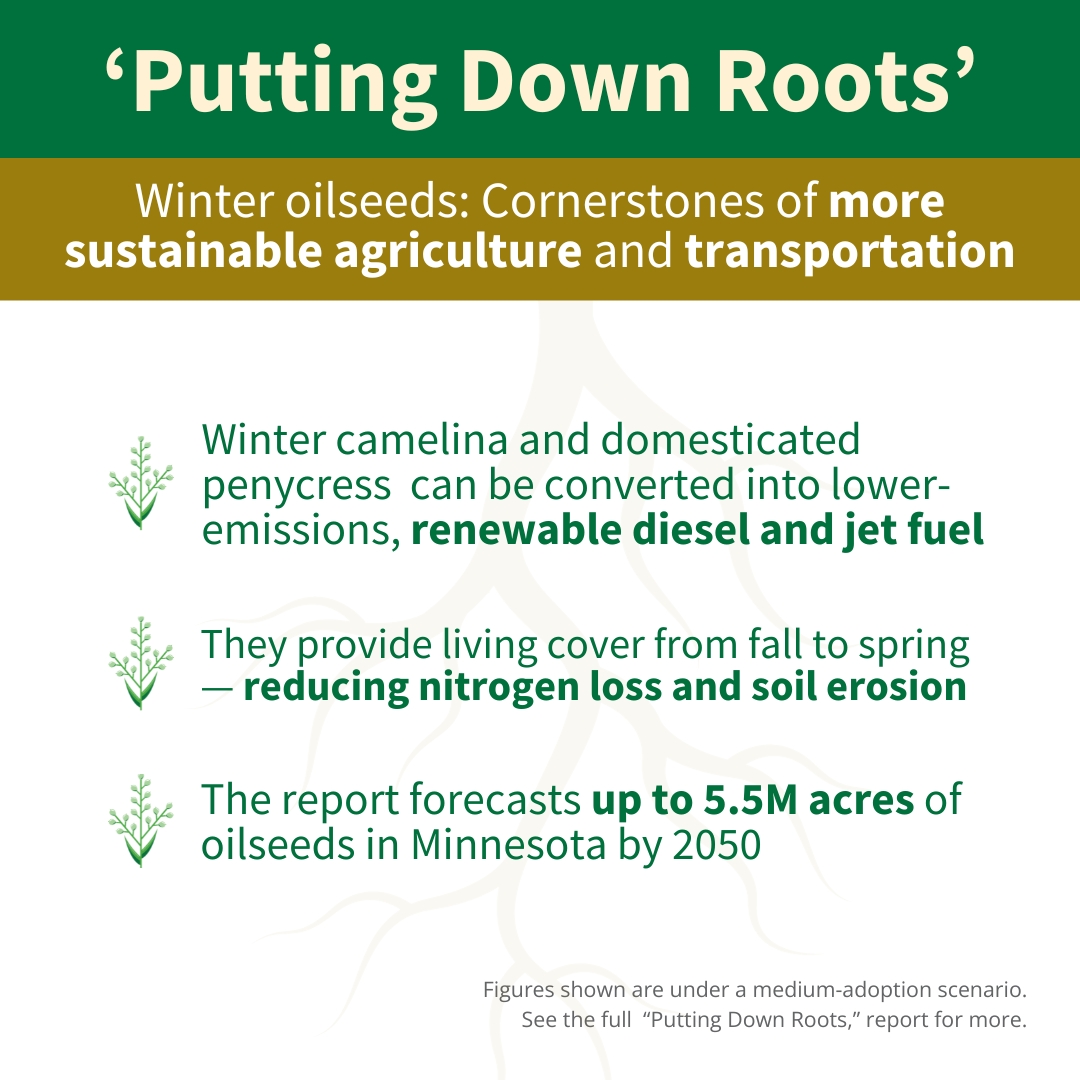

Two oil-producing plant species are emerging as potential biofuel game-changers for our region and the Mississippi River: winter camelina and domesticated pennycress.

These plants are:

- oil-rich and relatively easy to convert to high-demand fuels like renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel,

- “winter hardy” and able to survive Minnesota’s harsh climate,

- planted in fall and harvested in spring, covering the big brown spot and helping to dramatically reduce water pollution, and

- complimentary to conventional summer annual crops. Farmers could grow camelina and corn in the same rotation, for example, or pennycress and soybean.

Almost every modern crop is a highly customized version of its ancient ancestor, the result of generations — sometimes thousands of years — of intentional breeding. Camelina and pennycress are still in the development stage of this process. But these foundational traits make them exceptional candidates for success.

A tiny seed with a big impact, winter camelina is planted in the fall and harvested the following spring. (Photo by Dodd Demas for FMR)

How oilseeds protect the river

Pennycress and winter camelina (like other winter annuals) have important benefits for water quality, climate, and potentially even habitat for pollinators and other wildlife.

Research shows these crops do a great job of preventing two major water pollutants, nitrogen and sediment, from leaving farm fields.

While in the ground, winter oilseeds productively use excess nutrients that would otherwise enter water systems. At the same time, their roots hold the soil in place. Our landmark “Putting Down Roots” analysis found winter oilseeds could be cornerstones of a strategy to reduce nitrogen loss by 23% and soil erosion by 35%, simply by incorporating these and other clean-water crops into Minnesota farm rotations over the coming decades.

There is also an intriguing upside for climate benefits, which would help blunt some of the worst impacts of climate change on the river.

They can be processed to create renewable biodiesel or sustainable aviation fuel, reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation compared to fossil fuels. (Camelina-based jet fuel can reduce GHG emissions by more than 60% compared to petroleum-based jet fuel and is substantially more climate-friendly than other biofuel feedstocks.) This would be a game-changer for hard-to-electrify industrial applications like aviation.

Another critical aspect is what's known as “avoided land use change,” meaning it doesn’t take extra land to grow these crops. To make more biofuel from soybeans, we'd need to clear more acres in places like the Amazon rainforest, or repurpose existing acres from a different crop (which ultimately creates the same need to expand agriculture’s global footprint). Winter camelina and domesticated pennycress don’t have this problem. Because they grow on the same acres as the primary crop, just at a different time of year, that land pressure doesn’t exist.

Landscape resilience is also improved by diversifying the mix of crops and emphasizing crops that provide continuous living cover. Such systems help to build organic matter, beneficial fungi and microbial communities, and other indicators of soil health.

As we face an increasingly extreme weather regime, such resilience will be a major factor in the success or failure of our farm sector.

The "Putting Down Roots" report — released by Friends of the Mississippi River, the Forever Green Partnership and Ecotone Analytics — outlines why winter oilseeds are so promising. (Photo by FMR)

Why it makes sense for farmers

FMR is deeply invested in advancing cropping systems that provide continuous living cover, but there are plenty of nuances to that concept.

Perennial crops, with their extended lifespans and deeper roots, are extremely effective at addressing the environmental challenges of reducing farm runoff. They have an important, strategic role to play in protecting our waters. But it’s a big change — and a significant risk — for a farmer to replace acres of an established, commercial staple (such as corn) with a new perennial crop.

Winter oilseeds get around this systemic and financial predicament. Because they grow when conventional summer annuals aren’t on the landscape, integrating them into a crop rotation doesn’t require a farmer to make wholesale changes to their operation.

Economic incentive also exists, thanks to the current energy transition.

As greenhouse gas emissions continue to push the global temperature higher, destabilizing Earth’s climate more each year, we are seeing industries and governments begin to plot a course toward sustainability. Nowhere is this clearer than in the transportation industry, where biofuel producers are already benefiting from this course correction, since their products are (largely, though sometimes debatably) more climate-friendly than fossil fuels.

For certain sectors that face major barriers to electrification, such as aviation, biofuels present an enormous opportunity to decarbonize. Winter camelina and pennycress fit this profile better than almost any other biofuel feedstock, meaning that they could come to comprise a significant portion of the biofuels market.

In this sense, FMR is hitching a ride on the climate wagon: Industry will pay farmers for winter camelina and domesticated pennycress in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, just by virtue of existing on the landscape, these crops will also improve water quality and boost other environmental health indicators.

The flight path: How do we get there?

The agriculture sector, and commodity crop farmers in particular, are highly dependent upon a suite of federal policies — crop insurance, production tax credits and other incentives — that stabilize markets and mitigate risk to farmers and the companies that use their produce.

Farmland conservation, on the other hand, is largely the remit of “cost-share” programs, in which farmers and the public split the bill for practices, equipment or installations that reduce environmental harm.

A third set of policies and programs relates to things like pesticide laws, food safety certification and more.

In order to unlock the vast potential of winter annual oilseeds, FMR and the Forever Green Partnership are advocating for key changes to each part of this complex structure.

First, we’re pursuing opportunities to include oilseeds in established conservation cost-share programs like those offered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). In addition to funding, NRCS offers technical assistance and other resources to growers, and we can leverage the reach of these programs to help “early adopter” farmers experiment with camelina and pennycress, using their real-world experience to help design better production models and build familiarity with the crops.

Second, we are talking with federal agencies about how to extend the broader commodity “safety net” to oilseeds, specifically by making pennycress and camelina eligible for crop insurance. This is a long-term play that requires years of research, accounting and political advocacy, but achieving this goal would massively incentivize widespread farmer adoption.

Third, we are in the midst of designing a federal program that would jump-start industry investment and farmer adoption by underwriting some of the early costs of planting, harvesting and processing. By doing so, we can help to minimize the chicken-or-egg dilemma that faces any new crop: Without committed buyers, few farmers will take the risk of planting, but without guaranteed supply, few buyers will build the necessary infrastructure. Our program would create a safe and stable — but not permanent — bridge to profitably for both sides.

The state of Minnesota also has a unique, publicly funded grant program that helps to underwrite some of the costs of developing supply chains for novel crops such as winter camelina and pennycress. By focusing on local small- and midsized companies, this program — which FMR was instrumental in establishing — aims to broaden the roster of who can participate in these opportunities, which we hope enables new players with good ideas to enter the field.

Another priority is funding the basic research, development and commercialization of winter oilseed crops through the Forever Green Initiative. The success or failure of continuous living cover farming rests, in large part, on whether the crops themselves are viable in the marketplace, and so it is imperative that we support the work of Forever Green’s research into higher-yielding, hardier and more synergistic varieties of pennycress and camelina.

Become a River Guardian

Sign up and we'll email you when important river issues arise. We make it quick and easy to contact decision-makers. River Guardians are also invited to special social hours and other events about legislative and metro river corridor issues.